On immigration and real tragedies

by Gabriel Demasi

Story and pictures by Gabriel Demasi

Today marks one year of a hard time I’ve experienced.

Since then, so much happened. Very, very hard times. Times that defined the lives of millions of people and families. Or rather, death defined the lives of those who stayed. When someone asks me if I’m okay, I tell them “I’m okay, in quotes”. This tragedy of mine should go inside quotation marks too. But these other tragedies that have happened, these are the true ones, and they are so serious that I even feel ashamed of having been afraid, aimless, unlucky, or discriminated.

Miguel, João Pedro, George Floyd, the boys from Paraisópolis*: Marcos, Denys, Gustavo, Dennys, Gabriel, Mateus, Bruno, Eduardo, Luara. All dead. We know by whom.

In Brazil, officially, 180 people are murdered daily**. 75% of them are black. We know the number is much larger. Underreporting – good euphemism for the connivance between the State and the police.

Which reminds me of another tragedy: more than 47 thousand deaths by coronavirus reported so far in our country. We also know very well who is more exposed, who gets medical care and who dies without even being diagnosed, in a closed coffin, who is still having to use public transportation. We know who is most vulnerable. Meanwhile, the post of minister of health has been vacant for more than a month.

We’ve been at home for three months now. Last year, on this day, I was trapped in a space of about 500 square feet with other foreign men stopped in Barcelona. My anger at the time, as a Latin American who had been barred, prevented from entering, is worth nothing or very little compared to all the absurdity we have been living. But it turned out to be useful. It turned into a much bigger anger. I don’t think about traveling anytime soon. But destroying Borba Gato’s monument,*** hell, I’ve been thinking about it a lot.

Quote.

At 5 pm on June 19, 2019, I left Guarulhos International Airport, in São Paulo. On the 21st, at 8 pm, I was back. In the meantime, I was detained at Immigration in Barcelona. I carried my 27 years and my guitar, a friend on so many trips. I dressed plaid flannel pants, comfortable for travel, and a black hoodie.

In the last two years, I had graduated, experienced a breakup, moved to another city, quitted and started new jobs. I was desperately looking for a way out. At the time, I understood that it needed to be literally out. I decided to travel and stay at a friend’s house in Barcelona to see what happened. I wasn’t exactly thinking about staying in the country illegally, but it wasn’t exactly legal either. Perhaps I’d stay.

I had a return ticket for three months later. I had approximately one thousand euros, which I thought would last about a month. For the rest of the time, I would get by. Playing, working in some bar, doing some odd jobs, I still didn’t know how. The only thing I knew was that I could stay in Europe as a tourist for three months, and that was the only rule I stuck to.

Everything went smoothly, without delay, nervousness, mishap or unforeseen. I got off the plane and headed towards the queue. On the other side, European citizens. On my side, everyone who came from other places. In one of the armored glass windows there was a policewoman who looked kinder than the others. On her thirties, I guess, blond hair tied back. Even smiling. She called me.

– ¿Cuánto tiempo te quedas?

– Noventa días.****

Then she gave me that “gee” face. But how much money do you have? I showed her the money, my credit card and return ticket. It’s too long, what are you doing, where are you staying, one minute sir, I need to talk to my superior, please follow me. And from then on, I remained watched or imprisoned.

In the first room they left me waiting for a long time. Another policewoman. A long interrogation. Do you need an interpreter? No. Is your mom from Argentina? No. No. The same questions again.

So, she called the friend who was going to host me. She confirmed that she was waiting for me. She got told off over the phone.

– Look, ma’am, I see that you are a well-traveled, cultivated person, you’ve been here for three years now… You should know that things aren’t like that, you can’t just host anyone like that. You should have written a carta de invitación, attesting that he is staying at your house and taking responsibility for him.

More questions. I said that I had that money in hand, which was little, but that my family would send me more. That I was waiting for a scholarship I was applying for at a film school in Barcelona, but that it wasn’t certain yet. I also said that in a week I would go to Paris to visit another friend. That I had lived in Europe ten years ago and therefore had a lot of people to visit. I showed the tickets to Paris.

– Well, your friends are really nice, huh. They invite you, they pay things for you…

In the distance, I could hear the conversations of the other police officers, I could feel that public office atmosphere, which, I figured out then, was universal! At least Iberian, certainly. “The same thing every day… Let the Brazilians in!”, mocked one of them.

– Listen, Gabriel, personally I would let you in. But when you got here there was my boss, too many people around, now I just can’t do it. This is not the United States, no. We only require two things to get in, money and the invitation letter, and you don’t have either! Now that we have this procedure open, you will have to wait in the room. You will stay there, there’s a bed and a shower. And they will bring you food. Then a lawyer will try to help you and we’ll decide if you come back or not.

Escorted by two policemen, I went to look for my suitcase. I asked them if we there was somewhere I could smoke. Nope. It had been fifteen hours since I smoked my last cigarette.

– I used to smoke too. I can’t break protocol just so you can smoke. I don’t know what it’s like in your country, but here you can’t smoke indoors. See this as a good opportunity to quit!

They took me to the room. I must confess that until that moment I hadn’t realized that it would look like a prison. I didn’t know what to expect. Someone opened the door and I stayed there. A corridor with three or four doors on the left, where the bedrooms were. On the right, the bathroom. At the back a kind of dining room, with some chairs around a table. Not a single window. A grid behind the table.

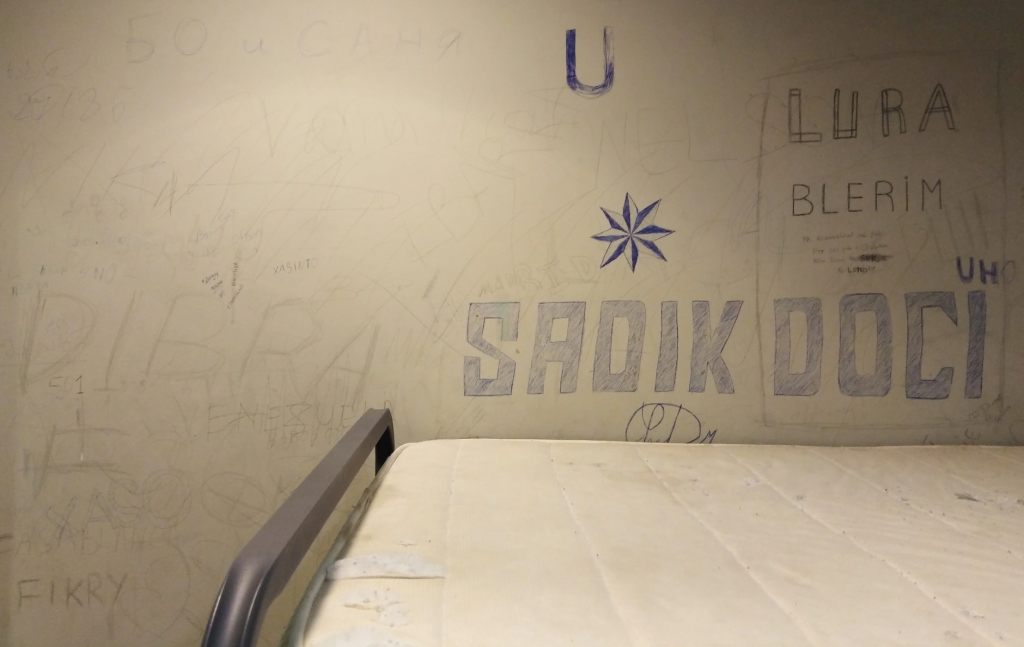

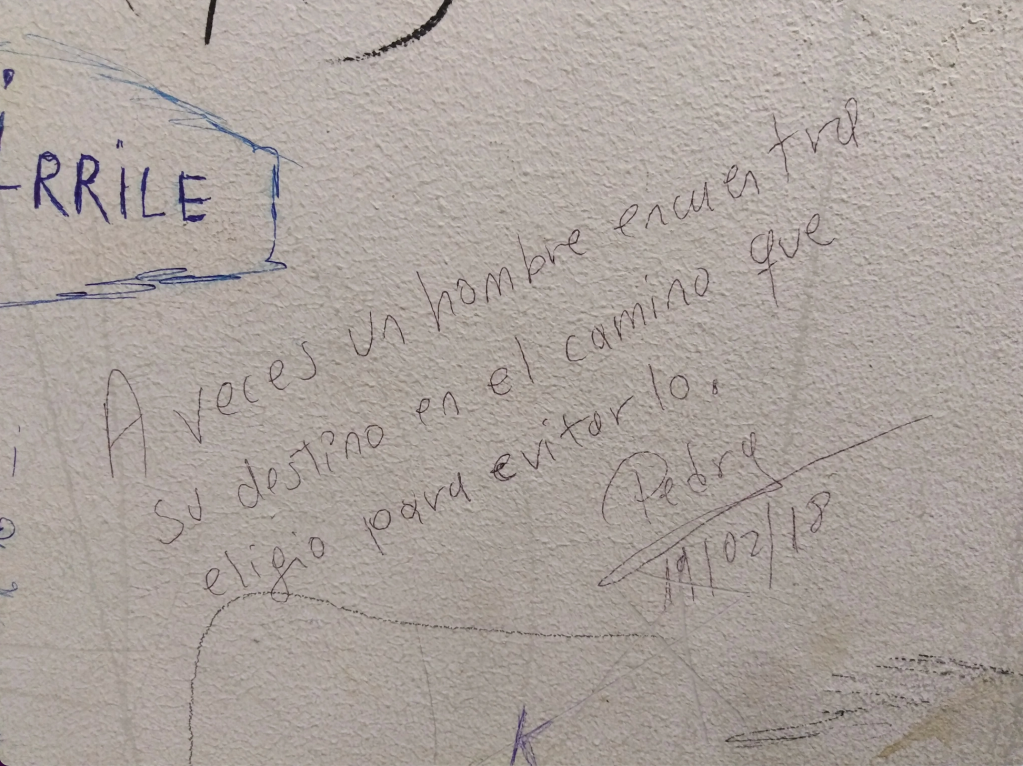

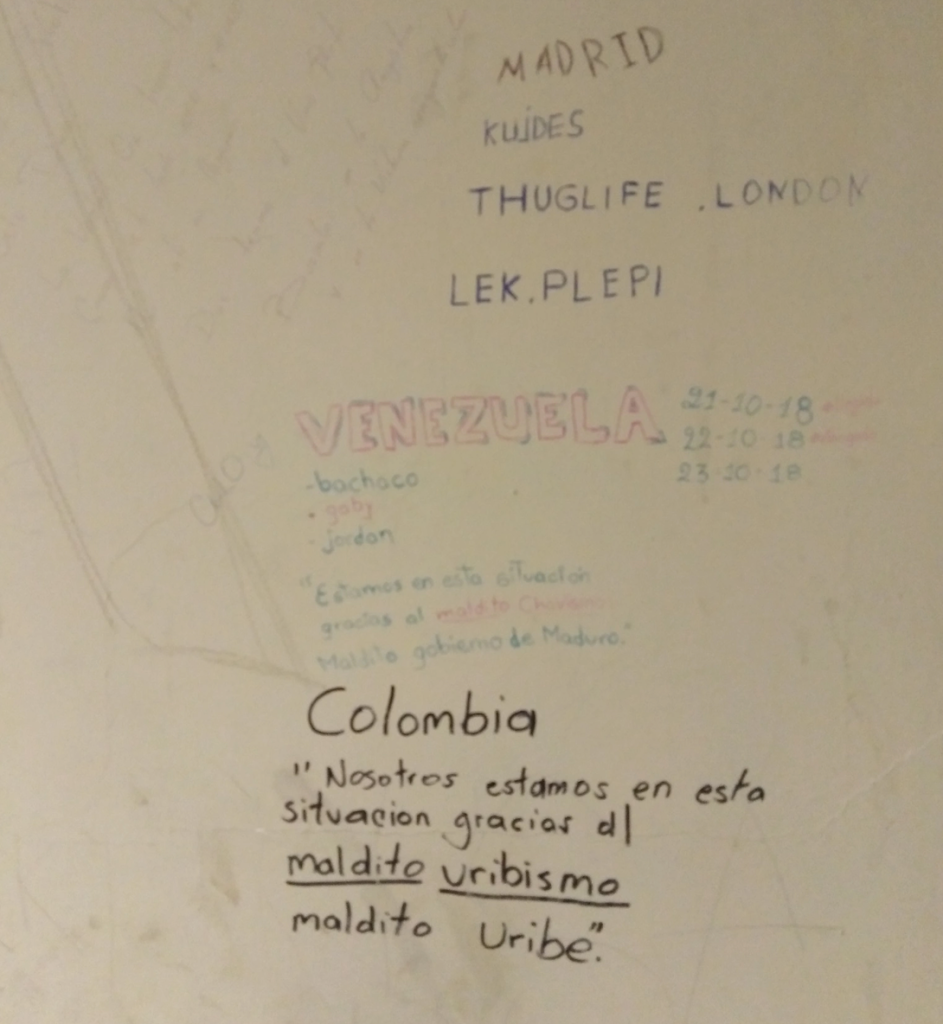

I looked for a free room and settled in. The walls are completely sprayed. Multiple languages. Drawings. Phrases. Outbursts. Marks of people who were there. The dates of their stay.

Disgusted with the mattress, I lay down anyway. I was exhausted and in shock. I didn’t want to open my suitcase. I put my hoodie over the pillow, stretched my body on the bed and slept. Outside, seven or eight fellow prisoners were walking around, speaking their languages, trying to call home. Men from Georgia, Turkey, Philippines, Albania, Colombia, Peru. And I.

Six hours later, someone shout my name. It was the lawyer.

We went to another police office. Again, I explained everything that had happened. She said there was nothing she could do. I gave the official statement to another police officer, who recorded everything I said. I said that my mother could go to the bank and send me the amount of money officially required, and that my friend could come and sign the document. The officer said I should have done this before.

– What you’re saying may even be true, but you should have done it before. We cannot wait for each of your family to sort things out in your countries. How many people would be waiting here? I’ll go see the chief now, he’ll have the final word.

And then he came back: you will return, sign here, here, here, your passport stays with me, we’ll give it to the flight attendant, you come back tomorrow. It was 5pm. I would have to spend the night there. The flight was the next day at noon.

– But look, nothing prevents you from coming back again, with all the right prerequisites. You can normally enter Spanish territory whenever you want.

In the morning, I was taken by car to the plane by two very happy police officers, who while driving sang, made jokes, they were more concerned with showing each other cool stories on Instagram.

I got in after all the regular passengers, through the back door of the plane.

After watching one movie after another on the plane, feeling like a zombie, dirty, hurt, lost, the next night, I was greeted by the Brazilian federal police. They took my passport from the flight attendant and wasn’t sure whether they had to register my entry, my exit, they didn’t know where to put me in their bureaucracy. Everything was so nonsense. I was nothing. Not a hippie, not a playboy, not a drug dealer. I was just someone lost and unaware. Naive, perhaps. Overbearing, perhaps. Just in case, they walked back and forth with my passport, searched my luggage once more. There was only guava paste, coffee beans, gifts I had taken from Brazil that I could never give.

After more than 30 hours being driven like cattle through all kinds of corridors, counters, rooms, parlors, cells, gates, turnstiles, I crossed the line of imaginary freedom. My mother and brother were waiting for me at the arrivals gate. She carried a black balloon, very suitable for the occasion, on which she had written: “We are with you, Gabri”.

Little did I know that after the following months of recovery, much worse things awaited me in the next year. In 2020, then yes, I would discover what a real tragedy looks like.

Unquote.

* Paraisópolis (“land of heaven”) is the second largest favela in São Paulo, home to over 100,000 people.https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2017/nov/29/sao-pauloinjustice-tuca-vieira-inequality-photograph-paraisopolis

** According to a report released in June 2019 by the Institute for Applied Economic Research (Ipea) and the Brazilian Public Security Forum.

*** Allusion to the monuments that were being torn down during the wave of protests that followed the murder of George Floyd. The statue of Borba Gato, a 17th century colonizer in Brazil, ended up being set on fire in July 2021, by a group called Peripherical Revolution (“Revolução Periférica”), a year later this text was written. https://www.brasildefato.com.br/2021/07/30/the-burning-of-a-statue-brought-to-lightthe-permanence-of-brazil-s-history-of-colonization

**** How long are you staying? / Ninety days.